And you’d be surprised… the answer goes further back than you might think.

So if you read Part 1, we left with a series of questions — all boiling around the conundrum of what I will call “the pain education lag.” This can be defined as the time it takes for the education to take an effect (i.e. reduction of aberrant pain). Essentially, you provide a treatment, but it’s possible for no effect to be seen immediately (and its also highly likely for this to occur in such a delayed fashion). And this is something that is significant. Other treatment effects take place immediately. Yet, with pain education this is not the expectation. Pain education results are only expected to be seen in the long term, but that brings us back to the question. Why?

If that question is not thought provoking for you, consider this: You have accessed the brain of your patient with chronic pain. You have instructed that brain that all pain is the result of the CNS acting as an alarm system response to potential threats. You have also told that brain that these signals can go awry and exist without any actual or legitimate input from the the peripheral system. Even more, you can quiz and test that brain to show conscious understanding of those facts. YET, with all of that…that same brain may continue to produce errant pain signals for some time. Perhaps in some cases — indefinitely.

So I ask again…why?

Why does effecting the brain that gives out those errant signals not have an effect? Why does conscious knowledge not equal subconscious neuro-physiologic activity?

Well…without knowing much more of the neurological details than I do at the present, I can deduce this could be generalized into some form of cognitive dissonance. That same brain you have connected with, has previously built up experiences — what it may call “proof” against your theory. So it refuses to accept a new reality. There may be millions and perhaps billions of neurons which are tagged and related to this brain’s current understanding of and relationship with pain.

Think of it this way: a life time of pain experiences can be represented as a graffitied wall. Many different images and paintings all construed into one large mural of related pain stories. This mural is intricately and seamlessly woven together. All of these individual graffitied marks in the brain’s conscious and subconscious are messages that support the hypothesis that pain is only related to structure and damage. That time you fell and scraped your knee as a child. The time you dislocated your shoulder during football practice. The time you had a not so pleasant dental hygienist cleaning your teeth and you noticed blood being drawn through the clear suction hose.

In order to overcome this “cognitive dissonance mural,” you would need to (hypothetically) erase all of the images on this wall. And I would say, additionally, you need to replace these images with salient demonstrations of pain as a perception. They can be made through metaphor or live demonstrations (e.g. rubber hand illusions) or examples of cold hard facts in scientific research; but nevertheless…there is this “delay.” And yes, I just pretty much explained the reason there is a delay (because we have to unlearn our current state). But why? Why do we have to unlearn?

Why did we learn pain to be something that it’s not?

There could be any number of causes (e.g. the rational/logical cartesian pain model), but I think outside of that — the main reason is poor pain education. We’ve made drastic errors in pain education and they go much further back than the clinic…they go back to the classroom. (And not just to graduate school.)

I challenge you: if you’re fortunate enough to still hold copies of your PT school notes — or perhaps even as far back as undergrad — take a look in all of the relevant course materials. My guess is you fall into one of two (or both) categories:

1) Pain neurophysiology is not discussed (excluding reference to any PT programs, though it’s still clearly not enough)

or…

2) Pain is spoken of incorrectly or confusingly.

Number two, in my estimation, is where we’ve messed up. It’s where we’ve missed the mark. (We’ve had correct models of pain science and neurophysiology dating back to the 1800’s.)

Examining my own course notes and text books, I saw conflicting signals. A neuroscience course that discusses pain in terms of “pain fibers,” yet a neuroscience text book that briefly attempts to dive into the complexity of pain as a perception in just two paragraphs (both of which are actually quite stunning despite their brevity). Looking at another PT course, I find both views within the same powerpoint presentation: the IASP definition for pain is provided, and on the very next slide comments about “pain fibers” are made.

If I go even further back, I find the very same in my undergrad anatomy and physiology textbooks. Two separate books for the same course; one discusses the IASP’s pain definition, and the other — pain fibers and free nerve endings sending pain signals up to the brain.

…

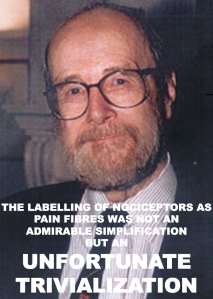

Now let me pause here. If you’re wondering, “What’s the big deal?” Then you may need some pain education yourself. These two world views on pain are fundamentally opposed. Therefore, they cannot co-exist, and furthermore, only one can be correct. Because while the experience of pain may be very subjective, the neurology of pain is not…it is central. Pain is in the brain…all the time. Nociceptors ≠ Pain Fibers.

Image Credit: Diane Jacobs

http://humanantigravitysuit.blogspot.com/2014/02/what-patrick-wall-said-about.html

…

On one hand, we have correct models of pain being taught: Pain is complex, it is a sensory/emotional experience, it occurs in the CNS.

On the other hand, we have: pain is simple, it occurs in the tissues then you become aware of it, it is always accurate.

You see what I’m getting at? Mixed signals. Add those on top of a lifetime of belief reinforcement: 1 + 1 = 2, or slam my knee(1) into the table(1) and get pain(2), and you get a confused populous. You get a 53 year old man with age related changes of the spine (better known as: “degenerative joint disease”) resulting in chronic pain requiring therapy, surgery, medication, or some combination of the three because we’ve failed to educate ourselves first.

So what’s left here? How do we cross this bridge? How do we get our patients (or maybe even practitioners) to understand pain?

Clearly we must do our part in the clinic (at the front-lines, if you will) explaining pain to our patients one-by-one, but this may be a design doomed to fail. Because if we do not address the problem of poor quality or lack of pain education at its source…it would seem the “pain cognitive dissonance mural” will naturally grow in the minds of young society — forming a never ending loop. Individuals will continue to grow into the cartesian model over and over, and we will continue to attempt to undo the city-block sized murals which have already taken place.

So for a solution other than widespread integration of pain science education throughout academia (K-12th up to grad school), I am at a loss. But maybe that’s just the solution we need. We teach elementary school students about cell biology, why can’t they learn about pain neurology?

-Spencer

Pingback: The Crossroads of Philosophy and Physiology (Part 1): The Pain Education Revelation | PTbraintrust

You have made a very nice contribution here, Spencer – Thank you.

The issue (with regards to developing a population that understands pain) is a challenging one. I have often wondered aloud – to the few people who care enough to listen – where we hack away at dualism in schools. Where might it fit in the existing curricula? English, Math, and History are non-starters. Science seems reasonable until you consider the classwork includes Geology, Life Science (Bio) and Physical Science (Physics). This leaves, in my estimation, health class.

I would propose that health class curricula be used to begin to cast doubt on dualism. Start the students off slowly in the their late elementary years, then hit them with some challenging thoughts later as juniors and seniors. I wager that students would be excited to learn how perception works. Great tricks and illusions could serve as wonderful examples from which dialogue can occur. As therapeutic educators later in life, how much easier would it be (reduced dissonance) if the patient can look back on experiences from earlier in their life they realize that what we are teaching them is supported by those previous experiences and have a more immediate A-Ha! moment.

I don’t think that people need to know about ‘pain’ early on, but our culture would benefit from an understanding of how our experience is all the output of a very fragile and often quirky neurological phenomena. All we need is someone earlier in life to unlock the door for us later on.

Of course – I am proposing that each state change their curricula, which is far more challenging than getting CAPTE to update their PT education standards, so I am certainly not optimistic – especially as schools throughout the country are making efforts toward increasing their teaching of dualism by introducing intelligent design (creationism).

Thanks again, Spencer.

LikeLike

Keith,

Thanks for reading and thinking with me. I will agree, pain education in grade school does not necessarily have to be the launching point. Perception as a reality can be thought provoking in its self, but perhaps (for doing some mental gymnastics) pain education may be a gateway towards making these conceptual thought patterns more relatable?

Pain is ubiquitous for all people (insert caveat for those people who genetically lack pain sensation), and given the $600 billion spent on it in the US each year, maybe it would be a good place to start? Nevertheless, I agree. Doesn’t HAVE to be the starting point. I had to figure out a way to wrap this post up neatly before I began to ramble. 🙂

Thanks again for reading.

LikeLike

Hi Spencer

Great article.I have been using a biopsychosocial approach for about 3 years now,.Whilst rewarding for certain patients who get the lightbulb moment I also get feedback from other practitioners who say the patient I saw previously told them that I had tried to tell them that their pain was in their head.

Firstly I realise that I am learning this new skill and improving my explanations,metaphors,similes and analogies on a weekly basis.Having attended Peter O Sulllivan’s Cognitive Functional therapy you can see a master of this approach and realise you are a student with lots to learn

But hardest of all is I am giving an “unusual “message in a clinic that is not known for this approach with other practitioners thinking you are a bit quirky.

I refuse to change.However in 15 years of practice I have never had a complaint against me ,but in the last year or so I have had a lot more grumpy patients.I should balance this with an equal amount of profound treatment results,which I know would not have had the positive outcomes by the old manual method.

I work in the UK but we have the same educational problems.I recently tried to get back into teaching and found students to be almost completely unaware of the BPS approach.

On the positive side it does appear to be seeping in,but this is what happens in a paradigm shift.It takes time.

LikeLike

Thanks for the input Graham.

The paradigm shift is the key, but are we capable of making it by only attacking it at one end of the problem (the patient w/ chronic pain)? I feel we’d be better served teaching the BSP model (or reinforcing it’s importance) in physio/physical therapy schools, but also hitting young society with pain science or at least the crazy, complexity of neuroscience to leave open the door for future pain education in the clinic (i.e. that is teach patient’s in the clinic, but also attack from different fronts).

As to the “its all in my head” patients, that can be difficult. I’ve wondered, in my limited experience, how many patients have walked off from my treatments thinking the same. I do find it useful to address that problem up front. I try to reconceptualize “the mind” for the patient as well. Instruct them that the mind and thoughts are as real as flexing the elbow or bending the knee. That just because the pain is in your brain, doesn’t make it less substantive. I have no long term follow up for these tactics though.

Anyway, thanks for reading and reflecting.

LikeLike

Pingback: Lost in Translation | PTbraintrust

Hi Spence,

just got pointed by a colleague towards your blog. Awesome and much needed ‘kick in the butt’ for many people. Although, it seems also very challenging to maintain a retorical correctness without accepting the full (philosophical) implications. An ontological issue with your text may arise when you quote ‘Pat’ (and McMahon) from their editorial in Pain that the term pain fibres is an unfortunate trivialisation, and yet you describe ‘pain signals’ and suggest that ‘pain is in the brain’ – either all must be wrong or neither of them can be due to the so-called ‘hard problem of consiousness’.

Most PTs refer back to the now-called ‘Explain Pain Revolution’ for backing up their claims about the need for more careful education, although several other sources have arisen over the years. What is really interesting from an academic AND clinical perspective is, that it seems that these claims can be made by anyone clever enough to grasp the conceptual change of an ‘explain pain’ perspective on pain. This could to some extend be similar to someone with a weekend course in massage therapy who comes up with an idea about how to change the PT-professional curriculum. This may actually be a great idea – but I would suggest that a deeper insight (education) about PT-education should be warrented prior to a full-fledged attack on the PT-profession. Likewise, I feel confronted by many (great bloggers) who apparently have a huge impact AND important messages to be told, but who unfortunately do not have sufficient knowledge about PAIN as a science to actually benefit a broader movement towards better educational needs. One very implication of ‘greate ideas with insufficient background understanding’ is that people with eg. medical or research background, who are trained in a critical appraisal of references and underlying concepts, consider most of the PT-based revolution as ‘unfortunate trivialisations’ – precisely the opposite of the intention!!

So as much as I agree with your comment on education I also believe that we first must look into our own ranks to ask the question of education/qualifications within PAIN SCIENCE that reaches beyond a mere conceptual understanding of pain in a biopsychosocial model.

Most greatful of your contribution and hoping that you consider giving me your view on the qualification problem.

Kind regards,

Morten Hoegh

LikeLike

Pingback: A Year In Review: II | PTbraintrust